We tend to think of parser generators as being used to implement the front-end of a programming language compiler, and having graduated from writing the desk-calculator program this is typically what we use them for. In this article we’ll take a look at another application of parser generators, specifically bisonc++, which is creating visualizations of state-transition diagrams for regular expressions.

Regular expressions (regexes for short) are concise ways of writing string-matching patterns. There are lots of operators for POSIX-compatible regexes, but the basis operators are (in order of precedence highest to lowest) the Kleene-closure (a* for zero or more a‘s), concatenation (ab for a followed by b) and set union (a|b for either a or b) . From these we get the identities a+ = aa* and a? = (a|ε) where epsilon derives the empty string. (Operators + and ? are assumed to have precedence equal to *, and cannot be used in combination with each other.)

The grammar for our parser of regexes (which would be ambiguous without operator precedence being specified) can therefore be formalized as:

R ← R* | R+ | R? | RR | R ‘|’ R | char

The representation of each node can be a C++ class, where the name of the node, its numerical ID and a list of edges can be implemented as:

class Node {

std::string name;

int id;

std::vector<std::list<Node>::iterator> edges;

public:

Node(const std::string& name, int id) : name{ name }, id{ id } {}

void addEdgeTo(std::list<Node>::iterator& node) {

if (std::find(edges.begin(), edges.end(), node) == edges.end()) {

edges.push_back(node);

}

}

void removeEdgeTo(std::list<Node>::iterator& node) {

if (auto iter = std::find(edges.begin(), edges.end(), node); iter != edges.end()) {

edges.erase(iter);

}

}

void setName(const std::string& n) { name = n; }

const auto& getName() const { return name; }

int getId() const { return id; }

const auto& getEdges() const { return edges; }

};

The set of edges actually uses a std::vector as it appears that std::sets of iterators are not allowed. To avoid the possibility of duplicate edges between nodes, addEdgeTo() only modifies the set of edges if the target is not found in the existing set. When dealing with node insertion (as discussed later), its counterpart removeEdgeTo() only attempts to modify the set if the target exists in the set. Getters and setters are implemented too.

Iterators are used instead of numerical indexes because they allow for insertion of nodes in a std::list<Node> without becoming invalidated, which is a side-effect of the way in which this container is implemented in the Standard Library. When concatenating regexes we need to keep a track of the start and end of it so that a compound expression such as (ab)* can be processed. This leads to the obvious semantic type for a regex expression parser to be std::pair<std::list<Node>::iterator,std::list<Node>::iterator>. It can also be assumed that the name of an edge is that of the node it leads to, or ε for an unlabelled node.

For the parser there are four tokens, CHAR, LPAREN, RPAREN and ERROR, together with four operators, BAR, PLUS, STAR and QUESTION. The first operator (having least precedence) is left-associative, the rest are right-associative. (Concatenation has precedence after BAR, but does not use an operator symbol.) All of these are exported to the header file Tokens.h.

Update 2024/10/05: It was found that attempts to use %prec for concatenation did not work correctly on regexes such as (aa|bb)+ so the code has been rewritten to use rule-based precedence.

The complete parser file grammar.y is shown below (apologies for lack of syntax highlighting):

%scanner-token-function scanner.lex()

%stype std::pair<std::list<Node>::iterator,std::list<Node>::iterator>

%token-path Tokens.h

%token CHAR LPAREN RPAREN ERROR BAR PLUS STAR QUESTION

%%

start : {

nodes.emplace_front("Start", nodeId++);

nodes.emplace_back("?", nodeId++);

nextNode = --nodes.end();

nodes.front().addEdgeTo(nextNode);

}

regex EOF {

nextNode->setName("Accept");

}

;

regex : disjunct

;

disjunct : disjunct BAR concatenate {

$$ = { nodes.emplace($1.first, "", nodeId++), nextNode };

for (auto& node : nodes) {

for (auto edge : node.getEdges()) {

if (edge == $1.first) {

node.removeEdgeTo(edge);

node.addEdgeTo($$.first);

}

}

}

$1.second->removeEdgeTo($3.first);

nextNode->setName("");

$$.first->addEdgeTo($1.first);

$1.second->addEdgeTo($$.second);

$$.first->addEdgeTo($3.first);

$3.second->addEdgeTo($$.second);

nodes.emplace_back("?", nodeId++);

nextNode = --nodes.end();

$$.second->addEdgeTo(nextNode);

}

| concatenate

;

concatenate : concatenate unary {

$$ = { $1.first, $2.second };

}

| unary

;

unary : unary STAR {

$$ = $1;

$$.second->addEdgeTo($$.first);

(--$$.first)->addEdgeTo(nextNode);

++$$.first;

}

| unary QUESTION {

$$ = $1;

(--$$.first)->addEdgeTo(nextNode);

++$$.first;

}

| unary PLUS {

$$ = $1;

$$.second->addEdgeTo($$.first);

}

| LPAREN regex RPAREN {

$$ = $2;

}

| CHAR {

$$ = { nextNode, nextNode };

nextNode->setName(scanner.matched());

nodes.emplace_back("?", nodeId++);

nextNode = --nodes.end();

$$.first->addEdgeTo(nextNode);

}

;

This can be compiled with the invocation bisonc++ grammar.y and an explanation of the rules follows.

Rule start uses a mid-rule action to create the first (“Start”) node and an edge to an unnamed node nextNode. It then reduces rule regex, followed by end-of-input, before renaming (the current) nextNode to the end (“Accept”) node.

After rule regex there are three further rules to create a regex: disjuct which recognizes |, concatenate which does not have an associated operator, and unary which handles *, ? and +; the resulting grammar is unambiguous and creates no shift-reduce or reduce-reduce conflicts (which bisonc++ would warn about):

unary STARmatches a trailing*for “zero-or-more”. More than one is handled by the node creating and edge to itself, and the zero case creates and edge from the previous node (obtained using--$$.first, which then requires++$$.firstto reset it correctly) to the following one.unary QUESTIONmatches a trailing?for “optional”, and adds the zero case only from (1)unary PLUSmatches a trailing+for “one-or-more”, and adds more-than-one case only from (1)concatenate unaryhandles concatenation. The value of$$is the full extent of$1and$2, no additional edges are needed to be created because of (7).disjunct BAR concatenateis the only way for the diagram to bifurcate, matching an infix|. This is the most complex rule as the graph needs to be rewritten by inserting a (blank) node. This is before$1.first, that is the beginning of the first parameter, and becomes the beginning position of the rule, withnextNodeas the end position. The arraynodesis traversed looking for edges to the node after the new one, and rewriting them as edges to the new blank node. The edge between the$1.secondand$3.firstis removed, that is between the end of the first parameter and the beginning of the second, assumed to have been created by (7). Edges to both parameters are created from the blank node, and then ε-edges to the second blank nodenextNodeare created. Finally a new unlabellednextNodeis created with an edge to it.- Parentheses are handled in the same way as for arithmetic expressions, as they provide syntactic grouping only.

- Encountering a single character renames

nextNodeand creates an edge to a new unlabellednextNodeat the back of thenodescontainer.

The scanner file scanner.l uses tokens generated from the parser file, but otherwise its implementation is simple:

letter [a-z]

%%

{letter} return Tokens::CHAR;

"+" return Tokens::PLUS;

"*" return Tokens::STAR;

"?" return Tokens::QUESTION;

"|" return Tokens::BAR;

"(" return Tokens::LPAREN;

")" return Tokens::RPAREN;

.|\n return Tokens::ERROR;

This file can be processed with the invocation flexc++ scanner.l.

Note that some hand-editing of the auto-generated Scanner.h, Parser.h and Parser.ih is necessary to allow the auto-generated files lex.cc and parser.cc to compile:

// Scanner.h

#include "Tokens.h"

// Parser.h

#include "Parserbase.h"

#include "Scanner.h"

#include "Node.h"

class Parser: public ParserBase

{

public:

Parser() = delete;

Parser(Scanner& scanner, std::list<Node>& nodes) : scanner{ scanner }, nodes{ nodes } {}

int parse();

private:

Scanner& scanner;

std::list<Node>& nodes;

std::list<Node>::iterator nextNode;

int nodeId{};

// Parser.ih

#include <list>

#include "Node.h"

#include "Parser.h"

inline void Parser::error()

{

std::cerr << "Bad regex.\n";

}

The driver reads strings of regexes from standard input and outputs GraphViz in textual format suitable for cut-and-pasting into a tool such as xdot:

#include "Node.h"

#include "Scanner.h"

#include "Parser.h"

#include <sstream>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Please enter a regex, or blank line to end:\n";

for (;;) {

std::string str;

getline(std::cin, str);

if (str.empty()) {

return 0;

}

std::istringstream input(str);

std::list<Node> nodes;

Scanner scanner(input);

Parser parser(scanner, nodes);

if (!parser.parse()) {

std::cout << "digraph regex {\n label=\"" << str << "\";\n rankdir=LR;\n node [shape=circle];\n\n";

for (const auto& node : nodes) {

std::cout << " q" << node.getId() << " [label=\"";

std::cout << node.getName();

std::cout << "\"];\n";

}

std::cout << '\n';

for (const auto& node : nodes) {

for (const auto& edge : node.getEdges()) {

std::cout << " q" << node.getId() << " -> q" << edge->getId() << " [label=\"";

if (edge->getName().size() == 1) {

std::cout << edge->getName();

}

else {

std::cout << "ε";

}

std::cout << "\"";

if (node.getId() == edge->getId()) {

std::cout << " dir=back";

}

std::cout << "];\n";

}

}

std::cout << "}\n";

}

}

}

Use of getline() and an std::istringstream allows for end-of-input markers to be passed to the parser. After basic configuration options a list of nodes (q0, q1,…) with labels is output (not necessarily in order, but this is not a problem in practice), followed by a list of appropriately labelled edges from each node. Where a node has an edge back to itself (as for a+ or a*) the arrow direction is reversed.

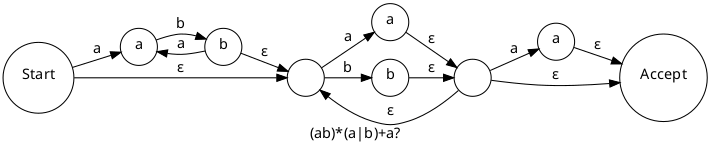

With the fairly complex regex (ab)*(a|b)+a? (that is: zero or more abs, followed by either a or b one or more times, followed by an optional a) the output produced is as follows:

Edit: Some compound regexes such as (a|b|c) fail to display satisfactorily (this may able to be resolved by use of a recursive BAR rule); I am looking to improve the parser so please leave a comment if you find other regexes which are processed incorrectly.

That’s all for this article, hopefully you’ll have become intrigued by the possibilities of using parser generators to solve programming challenges. It’s a form of functional programming, which might even generate an interest in true FP languages like Haskell. Source code for this article is available on GitHub.